|

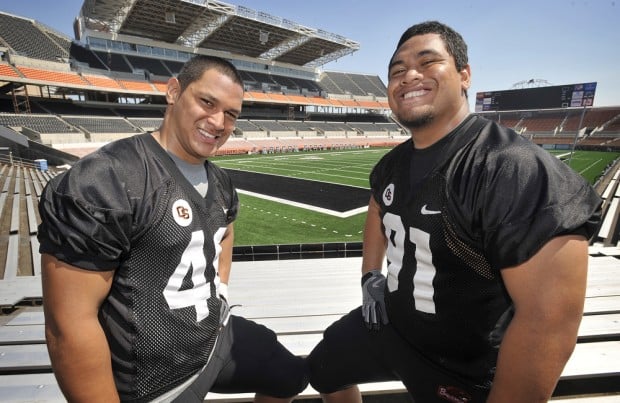

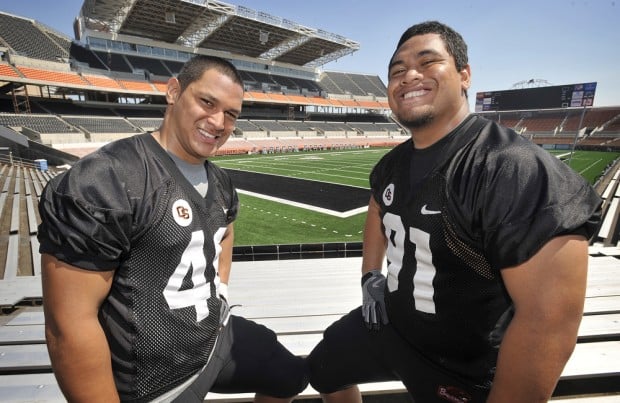

| Oregon State freshmen Rommel Mageo, left, and Noke Tago are attending school 5,000 miles from their home in Pago Pago, American Samoa. (Andy Cripe | Corvallis Gazette-Times)

|

Noke Tago’s first airplane ride was a long one.

A flight between American Samoa and the United States is roughly 15 hours.

If you’re lucky.

Tago said he flew eight hours to Hawaii, waited there for another eight hours and then made the five-hour trip to Oregon.

Tago and Oregon State teammate Rommel Mageo, also from Pago Pago, American Samoa, are both in Corvallis practicing with the Beavers’ football team.

It’s their first time away from home. And home is 5,000 miles away.

“Living a different life, it’s good for me because this is my first time I leave my parents and I stay away from my family,” Tago said. “So the first week I was homesick a lot and I missed my family.”

Mageo’s brother, Natanu, played for North Carolina State two years ago and had the benefit of talking to him before making the move.

“My brother played at N.C. State, so it was a big thing for me,” Mageo said. “He helped me out with a lot of things and he told me all about camp and everything.”

Moving halfway across the world is a big decision.

For Tago and Mageo, it’s a change that they were willing to make.

Few in American Samoa get a chance at college. Or more.

Career prospects are slim at home.

Football is their opportunity.

The American Samoa game

Football was introduced to American Samoa, an unincorporated territory of the U.S., in the 1960s.

While rugby is huge throughout Polynesia, including neighboring Independent State of Samoa, football stuck in American Samoa with the help of television.

The physical nature of the game turned out to be a natural attraction.

“In American Samoa, American football is big,” OSU defensive line coach Joe Seumalo said. “That’s their only form of entertainment.

“They’re raw at the game but they understand the physicalness of it and they love it. They’re no different than a lot of kids over here in the U.S.”

Until Pop Warner started up recently, most of the organized football was played at the high school level.

That means that most players from American Samoa who were good enough to come to the U.S. and play have been raw.

Mageo, a linebacker for OSU, has been playing the sport for five years.

He started in eighth grade.

“It wasn’t really around because we didn’t have youth football. It was only high school, so when you’re little, all you look up to is high school football,” Mageo said. “So when I was in eighth grade I really wanted to play football so I tried out.”

Tago played rugby when he was younger.

A defensive tackle for the Beavers, he’s now 6-foot-1, 290-pounds.

When he arrived in high school the football coaches took one look at him and convinced him to play.

“My freshman year I didn’t practice the whole summer,” he said. “I just come to school and register and the coaches wanted me because they saw me and I’m big. They wanted me to play for them.

“I had more confidence in myself because I played rugby.”

Seumalo said the rules governing football in American Samoa are limited, so the players are able to practice and play year-round.

The players are different as well.

Size is not lacking among the young men of American Samoa.

It’s easy to find linemen and linebackers.

“Football there is different from here,” Mageo said. “There it’s mostly about strength. It’s not really about speed, but everybody’s strong out there.”

The players condition constantly but weight training isn’t common.

Tago said he did a lot of work cutting trees and grass and did push-ups every night before bed.

“We have to do our chores. Every day we do our plantation, grow taro,” Tago said. “That’s where we get our muscle built.”

The recruiting game

Attracted by the size and potential, college coaches have looked for Samoan players for some time now.

Many players of Samoan descent, such as Troy Polamalu, Marques Tuiasosopo and the late Junior Seau, have made the climb to the NFL.

The University of Hawaii has been stocking its roster with Samoan players for years.

Access to the athletes who were already living in Hawaii or on the mainland was simple. Getting to those in American Samoa is a different story.

Film has often been used to evaluate the players.

Recruiting trips to American Samoa have always been tough for college coaches.

“Everyone knows about American Samoa, it’s just that you have flights that are limited, so if you go there, expect to stay there for a couple days because the next flight is three or four days later,” Seumalo said. “And in Samoa, you could probably do it one day, you could do all your reruiting in one day there. But with NCAA rules, these are the dates you can go out and if you go there, you kind of lose a couple days by being out there.

“We just have to be smart in how we do it.”

While there is a good group of American Samoan players who made the trip to the U.S. to play football this fall as freshmen, most of them went to junior colleges.

Four received full-ride scholarships from Division I teams.

Tago and Mageo were two. The other two are Robert Barber and Destiny Vaeao of Washington State.

“Coming here, it’s a big deal, so it was a big thing on the island,” Mageo said. “It was all over the newspaper and everywhere.”

OSU can provide the education and the base for a future career.

“It’s a way for us to get in and get some of those kids and develop those kids,” Seumalo said. “Because you can count the amount the kids that have grown up in the islands, whether it be Samoa or Tonga, that have made it here and played the game of football.”